Killing and Harming

- Pr 3, Killing a human being

- Pc 61, Killing an animal

- Pc 20, Pouring water containing living beings

- Pc 62, Using water containing living beings

- Pc 10, Digging soil

- Pc 11, Damaging living plants or seeds

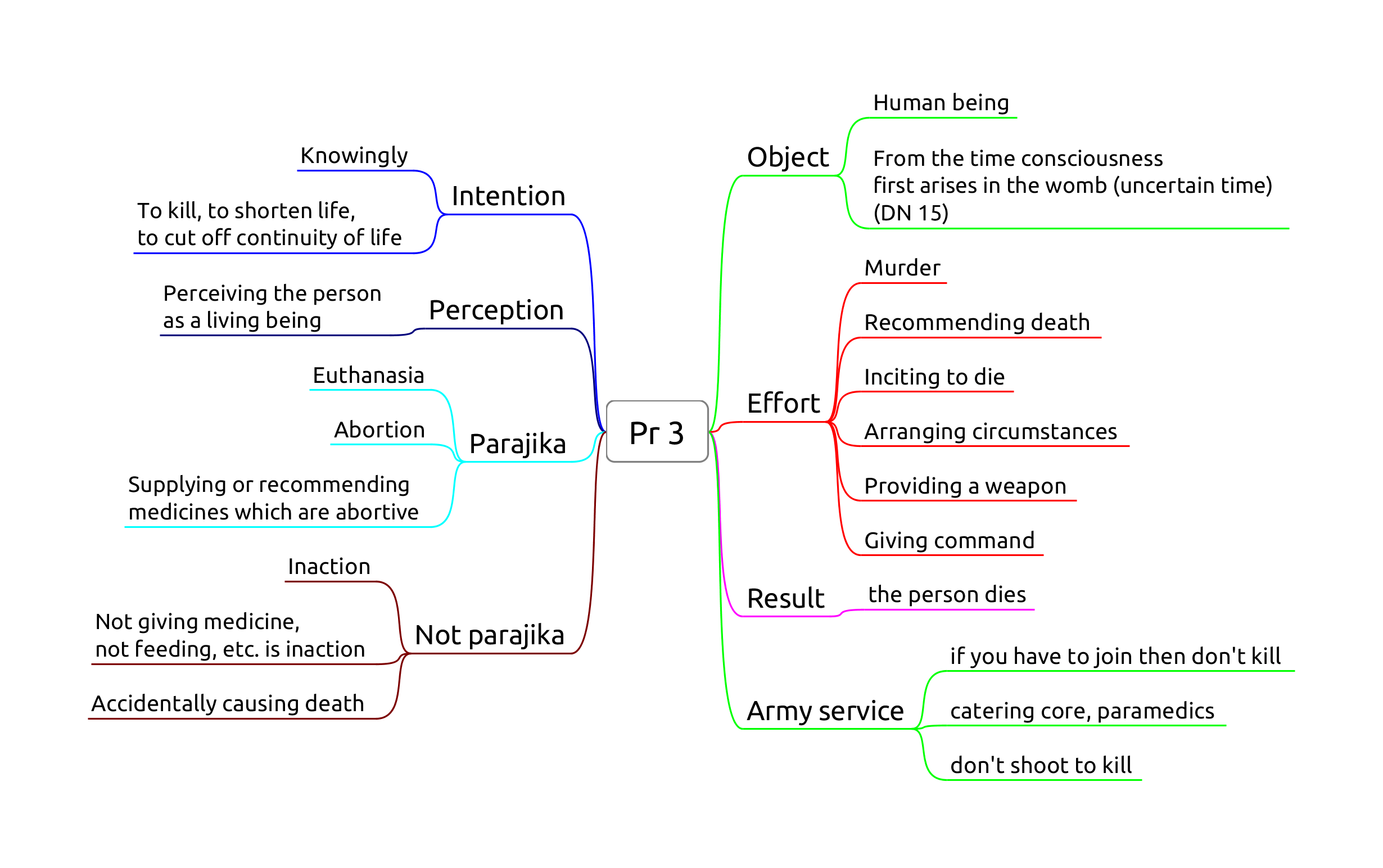

Pr 3, Killing a human being

Origin: bhikkhus develop aversion to the body and kill themselves or ask an assassin to kill them.

Recommending death or euthanasia can be pārājika if the instruction is followed. Hinting fulfils effort, such as "death would be better for you".

A human being is regarded as such from the time when the "being to be born" is established in the womb. This is an uncertain time, sometime after conception during embryo development. The embryo can't develop otherwise.

There is a distinction between recommending an action something which causes death in each case (abortion or active contraception) and something which causes death in some of the cases (a treatment which can go wrong). There is no offense in the second case, e.g. some people are known to die in car accidents, but it doesn't mean that a bhikkhu can't ask a person to drive.

Turning off life-support equipment: if the ill person stated their position on it beforehand, the doctors may be simply following his instruction.

When discussing topics around Pr 3, it is a good starting point if the bhikkhu clarifies his position (i.e. that he is pārājika is he recommends death), to prevent lay people interpreting his words as hinting.

A bhikkhu is technically allowed to report that a terminally ill person had said 'he wants to die', but one should be cautions. People may interpret it that he is recommending death, and also, the person might have changed his mind since that time.

Giving permission to the doctor to turn off the equipment is still not pārājika (not cutting off life, it ends on its own), although one might live with a doubtful heart afterward.

"If consciousness were not to descend into the mother's womb, would name-and-form take shape in the womb?" "No, lord."

"If, after descending into the womb, consciousness were to depart, would name-and-form be produced for this world?" "No, lord."

"If the consciousness of the young boy or girl were to be cut off, would name-and-form ripen, grow, and reach maturity?" "No, lord." (DN 15)

Pc 61, Killing an animal

Giving an order fulfils effort.

Result is a factor.

Doesn't include animals smaller than visible to the naked eye. Doesn't include accidents (sweeping). No room for "phrasing it right".

Origin: Ven. Udāyin is killing crows by shooting them with arrows, cutting their heads off and putting them in a row on a stake. The Buddha scolds him, "How can you, foolish man, intentionally deprive a living thing of life? ..." (Vibh. Pc 61)

Motive is irrelevant. Mercy killing by the owner, or euthanasia practices by vets fulfil effort. Having a pet means responsibility.

An alternative possibility for example to crush morphine pills, dissolve in water and feed it to the animal when it is in pain.

The local Animal Rights group may force the owner to allow the animal to be taken away and euthanised.

Acting in doubt, going ahead anyway is dukkaṭa. Such as when the bhikkhu thinks that cleaning an item may or may not kill living beings. Trying carefully not to kill insects while cleaning is not an offense.

Hitting an animal with the intention to kill it is a dukkaṭa offense. There is no offense if the intention was not to kill it, e.g. self-defense or warding off the animal.

Perception is a factor. Stepping on a twig with the intention to crush a snake is dukkaṭa.

Pc 20, Pouring water containing living beings

Knowing they will die from pouring it. It can also include knowingly adding poisonous substances.

If the water doesn't contain living beings, but the bhikkhu thinks it does, pouring or using it is dukkaṭa.

Giving an order fulfils effort.

Result is not a factor. Doesn't include accidents.

Can't water plants if one plans to eat its fruit, but may indicate it for others.

Kutis may use water moats around the stilts to keep out ants. One may treat the water with household chemicals to prevent larvae (e.g. mosquitoes) getting established in the water.

Pc 62, Using water containing living beings

Knowing they will die from using or drinking it, even accidentally.

Using water strainers or robe. Determining a corner of the saṅghāṭi as a water-filter.

Result is not a factor.

Pc 10, Digging soil

Origin: relates to the ancient belief that soil is alive, and loses life when dug up.

Object: 'genuine' soil.

Not genuine soil:

- dust from wind erosion

- pure or mostly rock, stones, gravel, sand are never 'genuine' soil

- burnt or already dup up soil is not 'genuine' until rained on for four months

If someone digs up the soil, a bhikkhu may shovel it into a wheelbarrow without offense.

Effort: Digging, burning, making a hole, or giving command to do it.

Putting tent pegs in the ground is to be confessed.

Non-offenses:

- unknowingly, unthinkingly, unintentionally

- indicating a general need or task

- asking for clay or or soil

- digging a trapped person or animal out

Allowance to indicate a need or general task to a lay person by 'wording it right' (kappiya-vohāra, allowable expression, or 'wording it right').

A specific command would be an offense ("dig a hole here"), but an indication ("dig a hole") of a desire or intent would not ("it would be good to have a hole for this post").

Pc 11, Damaging living plants or seeds

Origin: a bhikkhu cuts down a tree where a deva was living. The rule is formed later, when people complained of the bhikkhus mistreating one-facultied life.

Object: Living plant or seed. Lower plant life (i.e. mold, algae, fungi) is not included.

Effort: cutting, breaking, cooking, or getting others to do it.

Fruit with seeds: allowance to make allowable (kappiyam). Fruit can be kappied in one 'heap'.

To 'kappi' fruit is about the feelings of the donor, i.e. clarifying that they are not upset if the seeds get damaged.

When lay people are not explained the reason, they tend to think they have to do something unwholesome, such as killing the fruit or taking on bad kamma, so that the bhikkhu doesn't have to do it.

Knowingly eating un-kappied seeds is dukkaṭa only in the case when one is deliberately crushing the seeds. Cutting the seeds out or having no intention to crush them entails no offenses.

Lighting a fire on the ground (Pc 56), it can damage or kill the plants and creatures living there.

Non-offenses:

- unknowingly, unthinkingly, unintentionally

- asking a lay person for flowers etc. in general, or indicating a general task

- removing branches or leaves which are already dead

- can cut a trapped person or animal out

- counter-fire

Note: Pc 10 and Pc 11 prevents bhikkhus from engaging in agriculture, which is probably part of the intended results, although not their direct origin.

Notes: War and Peace

-

The Trolley Problem, "Should you kill one person to save five?"

-

Getting the Message, Thanissaro Bhikkhu (2006) (archive.org)

Killing is never skillful. Stealing, lying, and everything else in the first list are never skillful. When asked if there was anything whose killing he approved of, the Buddha answered that there was only one thing: anger. In no recorded instance did he approve of killing any living being at all. When one of his monks went to an executioner and told the man to kill his victims compassionately, with one blow, rather than torturing them, the Buddha expelled the monk from the Sangha on the grounds that even the recommendation to kill compassionately is still a recommendation to kill—something he would never condone.

- War and Peace, Bhikkhu Bodhi (2014) (archive.org)

The UN Charter sees physical force as a last resort but condones its use when allowing the transgressor to proceed unchecked would have more disastrous consequences.

The moral tensions we encounter in real life should caution us against interpreting Buddhist ethical prescriptions as unqualified absolutes. And yet the texts of early Buddhism themselves never recognize circumstances that might soften the universality of a basic precept or moral value. To resolve the dissonance between the moral idealism of the texts and the pragmatic demands of everyday life, I would posit two frameworks for shaping moral decisions. I will call one the liberative framework, the other the pragmatic karmic framework.

- Response to 'War and Peace', letters from Ajahn Thanissaro (2015)

The arguments are also misleading in that they casually dismiss the precept against killing because it is a moral absolute, as if all absolutes were naïve. Then they claim that there are circumstances in which the government’s need to protect its citizenry trumps the precept against killing. In other words, the need to protect a nation becomes the moral absolute, and yet there is no explanation as to where it gains its absolute authority, or why it’s more moral than not killing.

The arguments are further misleading in portraying their stance as “pragmatic,” implying that the Buddha’s approach is impractical. Actually, the Buddha’s absolutist approach is the only one that works when passions are aroused. A conditional or negotiable precept against killing is easily swept aside when people are overcome by anger or fear. Only a conscience that regards as a moral absolute the principle of no intentional killing—ever, at all—has a chance in holding the line against the passions.

Finally, the arguments are misleading in suggesting that their more “pragmatic” approach is ideal for people who want to approach liberation gradually. Actually, it’s a recipe for turning one’s back on liberation and marching off in the opposite direction. Ask any soldier suffering from the long-term effects of becoming a trained killer, and he or she will tell you that it’s no way to develop wholesome qualities of mind.

- The Reality of War, The Dalai Lama (2009) (archive.org)

Violence even 'for the good cause' has an unpredictable outcome, and lasting peace has to rely on trust. He avoids making a clear statement about killing human beings.

https://autonomousweapons.org/

A UN report found that autonomous drones armed with explosive devices may have “hunted down” fleeing rebel fighters in Libya last year. If true, the report chronicles the world’s first true robot-on-human attack.

Notes: Euthanasia

-

Terry Pratchett: my case for a euthanasia tribunal, theguardian.com (2010 Feb)

-

David Goodall ends his life at 104 with a final powerful statement on euthanasia, abc.net.au (2018 May)

-

'Disturbing': Experts troubled by Canada’s euthanasia laws, apnews.com (2022 Aug)

-

How Canada’s Assisted-Suicide Law Went Wrong, theatlantic.com (2023 May)